A year ago I described the basics of checkpoint queue latches:

After writing that article, I attended an excellent lecture by Mike Dietrich and Daniel Overby Hansen about noisy neighbors in a multitenant environment and how to make PDBs quieter and easier to live with in a larger society. During that lecture I thought about shared memory structures and semaphores — for example, how latches are shared across different PDBs…

Let’s investigate that in the context of checkpoint queue latches.

We already know that the function responsible for manipulating the checkpoint queue is kcbkgcql.

It is a small function and can be easily reverse-engineered. The part that’s relevant to us is:

ldrb w22, [x19, #200]

mov x2, #0x0

mov w1, #0x0

add x24, x19, #0x10

ldr x25, [x19, #264]

and w21, w22, #0x1

and x3, x21, #0xff

lsl x20, x3, #5

add x4, x20, x3

mov w3, w23

add x20, x25, x4, lsl #3

mov x0, x20

bl 0xb5f5360 <kslgetl>Fortunately, we live in wonderful times of LLMs and we can use them to make our lives easier. This code is, of course, trivial, and we don’t really need ChatGPT to analyze it; but I want to show you how easy it is when you know how to ask a proper question:

The prompt would be:

Below you will find ARM assembler code:

ldrb w22, [x19, #200]

mov x2, #0x0

mov w1, #0x0

add x24, x19, #0x10

ldr x25, [x19, #264]

and w21, w22, #0x1

and x3, x21, #0xff

lsl x20, x3, #5

add x4, x20, x3

mov w3, w23

add x20, x25, x4, lsl #3

mov x0, x20

bl 0xb5f5360 <kslgetl>

Assuming that x19 contains address of Oracle block header in buffer cache and 200 bytes from this header is column set_ds from x$bh, translate this code to python. The premise is that I have value of SET_DS from X$BH and I want to calculate latch address, which passed to kslgetl for acquiring a proper latch. And here is a nice answer:

Here’s the straight translation of what that AArch64 snippet does, distilled to the one thing that matters for the latch argument to kslgetl:

- Read set_ds (byte) from the block header.

- Take its least-significant bit.

- If that bit is 1, choose latch “slot” 33; if 0, choose slot 0.

- Latch slots are 8 bytes apart, so the byte offset is slot * 8.

- Add that offset to a base pointer read from [block_header + 264].

- Pass the resulting address to kslgetl.

Python translation

def latch_address_for_set_ds(set_ds: int, base_ptr_from_hdr_264: int) -> int: """ Compute the latch address that is passed to kslgetl. Args: set_ds: integer value of X$BH.SET_DS (byte, but int is fine). base_ptr_from_hdr_264: 64-bit value loaded from [block_header + 264]. This is the base of the latch array/structure. Returns: Absolute address (int) of the latch to pass to kslgetl. """ # w22 <- ldrb [x19,#200] ==> set_ds lsb = set_ds & 0x1 # and w21, w22, #0x1 slot = lsb * 33 # x4 = (x3<<5) + x3 -> 33 * lsb (0 or 33) offset = slot << 3 # ... , lsl #3 -> slot * 8 bytes return base_ptr_from_hdr_264 + offsetIf you only have SET_DS

If you don’t have the 64-bit value from [block_header + 264], you can still compute which slot it will use and the byte offset within that array:

def latch_slot_and_offset(set_ds: int) -> tuple[int, int]: lsb = set_ds & 0x1 slot = lsb * 33 # 0 or 33 offset = slot * 8 # 0 or 264 bytes return slot, offset

- slot will be 0 when SET_DS is even, 33 when it’s odd.

- The effective address passed to kslgetl is:addr = *(block_header + 264) + (slot * 8).

Everything else in your snippet (mov x2,#0, mov w1,#0, add x24,…, mov w3,w23) doesn’t affect the latch pointer; they’re other call arguments or dead/irrelevant for this specific calculation.

Actually, there’s a small twist — each block is protected by two checkpoint queue latches: if the first one is taken, the second one is used.

You can write a simple query that computes both checkpoint queue latches for each block of a table.

In my test environment I have two PDBs — RICK1 and RICK2. Each has the table HR.EMPLOYEES, a small table with only two data blocks. Let’s inspect the checkpoint Q latches after selecting blocks from that table.

We use the following query:

set linesize 200

set pagesize 100

column name format a10

select p.name, b.dbablk,

to_char(case when mod(dbablk, 2) = 0 then to_number(set_ds,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX')

else to_number(set_ds,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX')+264

end,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX') as primary_checkpoint_q_latch,

to_char(case when mod(dbablk, 2) = 0 then to_number(set_ds,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX')+264

else to_number(set_ds,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX')

end,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX') as secondary_checkpoint_q_latch

from x$bh b, cdb_objects o, v$pdbs p

where o.object_name='EMPLOYEES'

and state!=0

and b.obj=o.data_object_id

and o.con_id=b.con_id

and o.con_id=p.con_id

and b.dbablk in (38452, 38453)

order by primary_checkpoint_q_latch, dbablk, o.con_id

/SQL> @calculate_latch.sql

NAME DBABLK PRIMARY_CHECKPOIN SECONDARY_CHECKPO

---------- ---------- ----------------- -----------------

RICK1 38452 1486E8168 1486E8270

RICK2 38453 1486E8270 1486E8168

RICK1 38453 1486E8B30 1486E8A28

RICK2 38452 1486E9BA8 1486E9CB0As we can see, block 38452 from RICK1 and block 38453 from RICK2 are being protected by the same set of latches:

- 1486E8168

- 1486E8270

We can verify that those are a proper latch addresses:

SQL> get latch_names.sql

1* select name from v$latch_children where addr in ('00000001486E8168','00000001486E8270')

SQL> /

NAME

--------------------------------------------------

checkpoint queue latch

checkpoint queue latchSo we have demonstrated that two different pluggable databases can use the same set of latches to protect their blocks. What would happen if one database held those latches constantly?

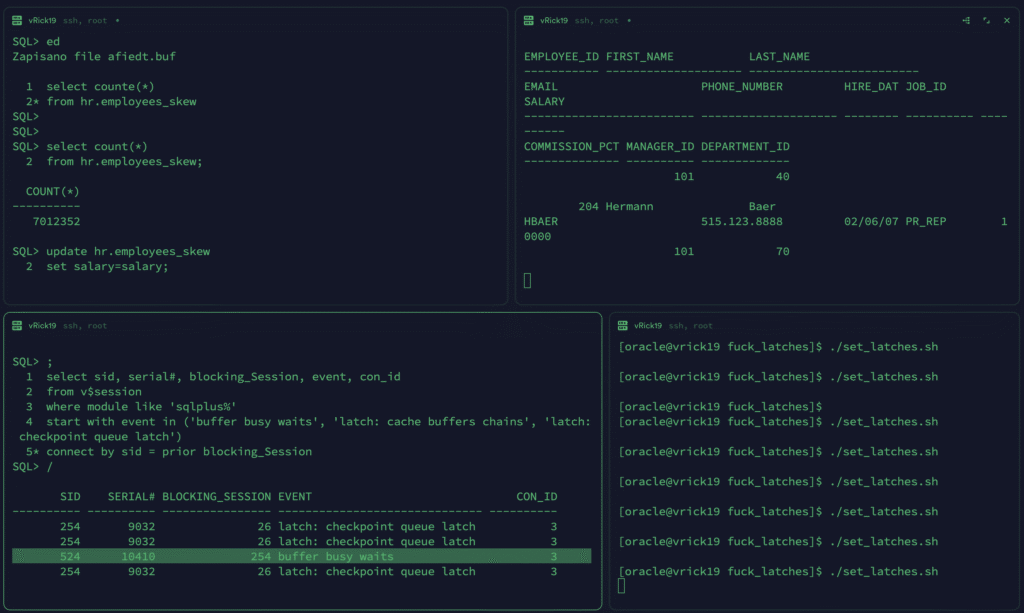

I created a larger table in RICK1: HR.EMPLOYEES_SKEW

SQL> select count(*)

2 from hr.employees_skew;

COUNT(*)

----------

7012352I also prepared scripts to force RICK2 to acquire a latch at a specific address:

[oracle@vrick19 fuck_latches]$ cat latch2.sql

alter session set container=rick2;

select userenv('sid') from dual;

oradebug setmypid

oradebug call kslgetl 0x&1 0x0 0x0 0xc1e

pause[oracle@vrick19 fuck_latches]$ cat set_latches.sh

#!/bin/bash

while IFS= read -r line

do

tmux new -d sqlplus "/ as sysdba" @latch2.sql ${line}

done < <(sqlplus -S "/ as sysdba" @list_latches.sql)

read

tmux kill-server[oracle@vrick19 fuck_latches]$ cat list_latches.sql

set heading off

set pagesize 0

set feedback off

with v_l as

(

select b.con_id, b.dbablk,

to_char(case when mod(dbablk, 2) = 0 then to_number(set_ds,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX')

else to_number(set_ds,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX')+264

end,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX') as primary_checkpoint_q_latch,

to_char(case when mod(dbablk, 2) = 0 then to_number(set_ds,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX')+264

else to_number(set_ds,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX')

end,'XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX') as secondary_checkpoint_q_latch

from x$bh b, cdb_objects o

where o.object_name='EMPLOYEES_SKEW'

and state!=0

and b.obj=o.data_object_id

and o.con_id=b.con_id

)

select primary_checkpoint_q_latch

from v_l

union

select secondary_checkpoint_q_latch

from v_l

/

exitThe set_latches.sh script launches multiple tmux sessions with sqlplus, each holding a latch address tied to EMPLOYEES_SKEW blocks.

Now let’s start a massive update from RICK1:

SQL> update hr.employees_skew

2 set salary=salary;From another session of RICK1 I will run a simple SELECT * FROM HR.EMPLOYEES_SKEW;

Let’s see what will happen for the select:

As you can see, the SELECT statement is waiting on buffer busy waits, which is a consequence of latch: checkpoint queue latch. The session 26 is not present in my view, because it won’t be visible from RICK1.

It will be visible only from RICK2 or from CDB level:

SID SERIAL# BLOCKING_SESSION EVENT CON_ID

---------- ---------- ---------------- ------------------------------ ----------

254 9032 26 latch: checkpoint queue latch 3

26 48485 SQL*Net message from client 4

26 48485 SQL*Net message from client 4

524 10410 254 buffer busy waits 3

254 9032 26 latch: checkpoint queue latch 3

26 48485 SQL*Net message from client 4

26 48485 SQL*Net message from client 4Usually checkpoint queue latch is being taken during commit, thanks to private redo strands and IMU.

So it would be possible to degrade the performance of the whole CDB by doing many commits (or rollbacks) — and this is only from the checkpoint queue / redo perspective. There are more latches and more shared structures that can cause nightmares.

Let’s prepare a commit overkill:

declare

cursor c_sql is

select rowid as rid from hr.employees_skew;

type t_rowid is table of c_sql%ROWTYPE index by pls_integer;

v_rowid t_rowid;

begin

open c_sql;

fetch c_sql bulk collect into v_rowid;

close c_sql;

for i in v_rowid.first..v_rowid.last loop

update hr.employees_skew set salary=salary+1 where rowid=v_rowid(i).rid;

commit;

end loop;

end;

/On RICK1, from one session I created an active transaction which will make any other session to create CR blocks in a buffer cache:

SQL> update hr.employees_skew set salary=salary;

Zaktualizowano wierszy: 7012352.

SQL> show con_name

CON_NAME

------------------------------

RICK1From another session of RICK1 I will perform a simple SELECT * FROM HR.EMPLOYEES_SKEW;

This is a list of unique wait events when RICK2 is being silent:

[oracle@vrick19 fuck_latches]$ cat /u01/app/oracle/diag/rdbms/rick/rick/trace/rick_ora_8946.trc | grep WAIT | grep -v Net | awk -F\' '{print $2}' | sort -u

Disk file operations I/O

latch: object queue header operationBut when RICK2 becomes noisy and performs thousands of transactions:

[oracle@vrick19 fuck_latches]$ cat /u01/app/oracle/diag/rdbms/rick/rick/trace/rick_ora_8763.trc | grep WAIT | grep -v Net | awk -F\' '{

print $2}' | sort -u

Disk file operations I/O

latch: cache buffers chains

latch: redo allocation

log buffer space

log file switch (checkpoint incomplete)

log file switch completionA big difference!

This was when neighbor was quiet:

SQL ID: dgd9achf2jp7y Plan Hash: 4089363840

select *

from

hr.employees_skew

call count cpu elapsed disk query current rows

------- ------ -------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ----------

Parse 2 0.00 0.00 0 0 0 0

Execute 2 0.00 0.00 0 0 0 0

Fetch 600877 1.97 13.36 0 10260251 0 9013113

------- ------ -------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ----------

total 600881 1.97 13.36 0 10260251 0 9013113This happened when neighbor was noisy:

SQL ID: dgd9achf2jp7y Plan Hash: 4089363840

select *

from

hr.employees_skew

call count cpu elapsed disk query current rows

------- ------ -------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ----------

Parse 1 0.00 0.00 0 0 0 0

Execute 1 0.00 0.00 0 0 0 0

Fetch 467492 1.73 147.71 0 7982614 0 7012352

------- ------ -------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ---------- ----------

total 467494 1.74 147.71 0 7982614 0 7012352Conclusion? Be careful what you integrate together! And always analyze database performance from CDB perspective. If you are having problems with overall performance understanding – JAS-MIN can help you 😉